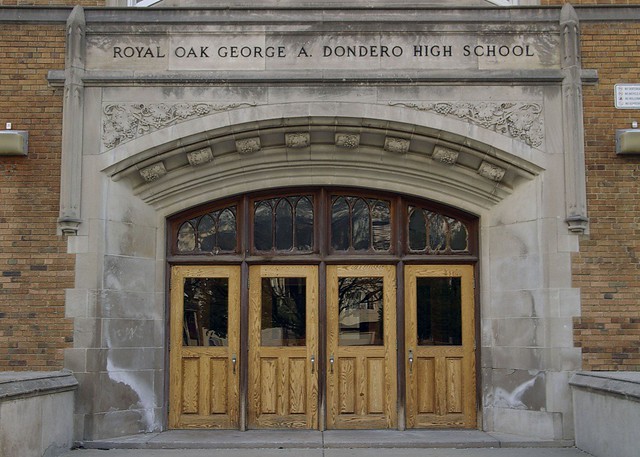

Its heyday was the mid-70s, when 2400 students lived within walking distance of the three-story building known as Dondero High School. A unique feature of the schedule at that time was the lunch period, which included two shifts where students went to class for a while, left for lunch, then returned to the same class for the second half of the lesson.

Royal Oak was a mid-sized suburb with a smalltown heart. The stores were locally owned, everybody knew everybody, and any student who misbehaved in school didn’t have to worry about the school calling home; the town grapevine would send the news Mom and Dad’s way well before the student ever got there. Even when I started there in the mid-80s, one teacher made home visits with every student who failed the first test in his class, and the highest award presented at honors convocation was named after a beloved local hero. Walking in his footsteps was the highest aspiration a student could hope to achieve.

I had the good fortune to work with several teachers who had spent their careers at the school, starting in the Eisenhower administration. They’d taught this generation’s parents, and sometimes knew their grandparents—and if you think that doesn’t impact the way you teach or learn Shakespeare or the Revolutionary War, you really don’t understand much about schools. For fun, a couple of them would debate the meaning of obscure words in the staff room at lunch. These instructors had the brainpower to teach at the finest prep schools in the country, but their hearts called them to something more compelling.

Dondero was named after an alumnus who served in Congress, but his fame was eventually eclipsed by another local boy, who often came back just to say hello to his old teachers. I caught a glimpse of him, as he floated down the halls in a brown duster that was worth more than my full-year’s salary. But Glenn was the real deal, a south Royal Oak kid who never forgot his roots, whose visits were valued for the person he’d always been, not the person he’d become. The street running south of the school was renamed Glenn Frey Drive when he passed away. You did that kind of thing in south Royal Oak.

By the time I got there, Dondero’s population had dwindled to 1000 students. The decline continued, leading the district to decide in 2006 to go back to one high school. They opted to house it in the newer high school on the north side of town, but even after announcing Dondero’s closure two years ahead of time, over 600 students remained at Dondero, including ninth- and tenth-graders. As one administrator put it, parents figured two years of a Dondero education beat none at all.

I worked in several high schools in my career, including some with national reputations for excellence. But when you work at a place where teachers say hi to every student by name in the hallway (and get a response); when every teacher intuitively understands their first objective every day is to give each student the opportunity to feel valued, and capable of learning; where the only thing that brought students together was their zip code, but the experience left them with an enlarged sense of self and family, you understand how the ideals of public education can be brought to life, and you hold your head a little higher, while your heart is humbled at the chance to have been part of it all. That stays with you forever.

Accidental Nap

I’d eaten a pear snack

While locking up

And truly meant to brush

But she wore a red-striped nightshirt

And the bed was freshly flannelled

So Papa joined Mama

For what I thought would be a minute.

Then the hazy warmth

Of a dozen dreams

Gave way to icy sunbeams

And frosty floorboards.

I wished I’d mastered the timing switch on the thermostat

And taken the time to dejuice my molars.

Imagine my surprise

When morning breath was absent

Replaced by the aura of pear.

Well done, Bartlett.

Like what you see? Subscribe for free!

One response to “Dondero”

-

You and your students were very fortunate. Thanks for sharing a piece of the “Good Old Days”. John

LikeLike

Leave a comment